I opened Pandora's box, or rather Pandora's boxes. When I returned to my "Mexico Years" to explore the possibility of writing another memoir, I decided to dig out saved journals, photos, and letters.

My husband and

I have lived in a very small house close to twenty-five years. Before that I

lived in an even smaller cottage, and before that a one-bedroom Seattle

apartment after five years and five months in two postage stamp apartments in

Mexico City. I am amazed at how much stuff I saved, how easy it was to stash

this stuff into nooks and crannies, and how overwhelming it became when it was

time to take a peek.

The first box I

found was pink cardboard covered in tiny white hearts that once held my daughter's

dress-up collection. I was searching for Judi's letters. I met this British

friend in Mexico and saw her again in England shortly before her death when we

joked of writing The Ex-Mexican Wives Club. Stashed in the laundry room and

crammed with yearbooks, merit badges, pictures, cards, letters, the box

contained only a few of Judi's later letters. I was disappointed.

I dug deeper

into the laundry room, the backs of closets, the crawl space under the stairs.

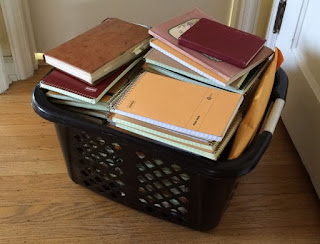

On the floor of the linen closet, shoved deep behind my basket of journals, I found a large plastic storage bin of letters.

Before

settling into reading mode, I decided to give the house another sweep. Sure

enough one more box was lodged behind a box of books on the floor of my clothes

closet. I returned to the dining table and added this new box full of letters

to the plastic bags. I haven't gone up into the attic yet, but I'm reasonably

confident there's nothing there. Yet as I write these words, I know I will

check.

I've begun

reading these letters. I sort the collection in each plastic bag into chronological

order and begin with the earliest. The letters reveal timelines and facts,

experiences and emotions of the writer as she or he responds to my prior

letter. I have only one side of these conversations, with two profound

exceptions, but even that is plenty to fill in gaps and prod faded memories.

The

two exceptions? Mom and Maureen. I didn't know how much my mother saved until I

spent weeks sorting and emptying her house after my siblings and I made the

difficult decision to move her into a dementia care facility. There was much I

didn't know about my mother, but uncovering baby books, hospital bracelets, report

cards, school projects, and saved letters from each of her nine children

shocked me to my core.

At the time I

was on a mission to sort and empty the house. I created nine piles, one for

each sibling. It was not a popularity contest. There was no favorite child. The

piles varied in size largely based on the physical distance between parents and

kid, and how often we each wrote home. I didn't read the letters I'd sent to my

Mom and Dad through the years, or those I'd sent to my youngest sister. It was

too soon, too painful. I put them in a box and stashed them away.

Now I will

read those letters. All of them. In my Pandora's boxes, I will find the memories

and truths hidden in words penned in a world before email made the art of

letter writing obsolete.

Enjoying

this blog series? To receive email

notification of new posts, please subscribe by entering your email address in

the box in the upper right column. Thanks!

Prior posts in this series:

Prior posts in this series: